This is a note for the course Writing in the Sciences, offered by Stanford and taught by Dr. Kristin Sainani. I deeply appreciate her selfless dedication to this course. Since I am still an undergraduate student, I have chosen to omit certain sections, such as those on “Grants” and “Social Media.”

If you notice any errors or have suggestions regarding this note, feel free to email me. You can find my contact information on my homepage.

Authored by Bingkui Tong

December 30, 2024

Section 1Principle of Effective Writing:Cut the Clutters: Section 2Use the active voiceWrite with VerbsA Few Grammar TipsSection 3Semicolon ;Parentheses ()Colon :Dash —ParallelismParagraphsA Few More TipsSection 4Overview of the Writing ProcessThe Pre-writing StepThe Writing StepRevisionChecklist for the Final DraftSection 5Tables and FiguresResultsMethodsIntroductionDiscussionAbstractSection 6PlagiarismAuthorshipSubmission processDoing a peer reviewPredatory JournalSection 7Writing Review ArticlesWriting letters of recommendationPersonal statementSection 8Talking with the mediaWriting for general audiencesWriting a science news story

Section 1

Principle of Effective Writing:

- Cut unnecessary words and phrases; learn to part with your words!

- Use the active voice (subject + verb + object)

- Write with verbs: use strong verbs, avoid turning verbs into nouns, and don’t bury the main verb

Cut the Clutters:

TIPS:

- Be vigilant and ruthless

- After investing much efforts to put words on a page, we often find it hard to part with them

- But fight their seductive pull: Try the sentence without the extra words and see how it’s better — conveys the same idea with more power

- Eliminate the negatives

- Eliminate there are/is

- omit needless prepositions

Common clutters:

Dead weight words and phrases (delete all of them and use citation to do the same thing)

- As it is well known

- As it has been shown

- It can be regarded that

- …

Empty words and phrases

- basic tenets of

- methodologic

- important

- …

Long words and phrases that could be short

Unnecessary jargon and acronyms

Repetitive words or phrases

- studies/examples

- illustrate/demonstrate

- challenges/difficulties

- successful solutions (there isn’t unsuccessful solutions😂)

Adverbs

- very, really, quite, basically, generally, etc.

Examples:

Example 1:

- Before: “This paper provides a review of the basic tenets of cancer biology study design, using as examples studies that illustrate the methodologic challenges or that demonstrate successful solutions to the difficulties inherent in biological research”

- After: “This paper reviews cancer biology study design, using examples that illustrate specific challenges and solutions.”

Example 2:

- Before: “As it well known, increased athletic activity has been related to a profile of lower cardiovascular risk, lower blood pressure levels, and improved muscular and cardio-respiratory performance.”

- After: “Increased athletic activity is associated with lower cardiovascular risk, lower blood pressure, and improved fitness.”

- Better: “Increased athletic activity lowers cardiovascular risk and blood pressure, and improves fitness.”

Example 3:

- Before: “The experimental demonstration is the first of its kind and is a proof of principle for the concept of laser driven particle acceleration in structure loaded vacuum.”

- After: “The experiment provides the first proof of principle of laser-driven particle acceleration in a structure-loaded vacuum.”

Section 2

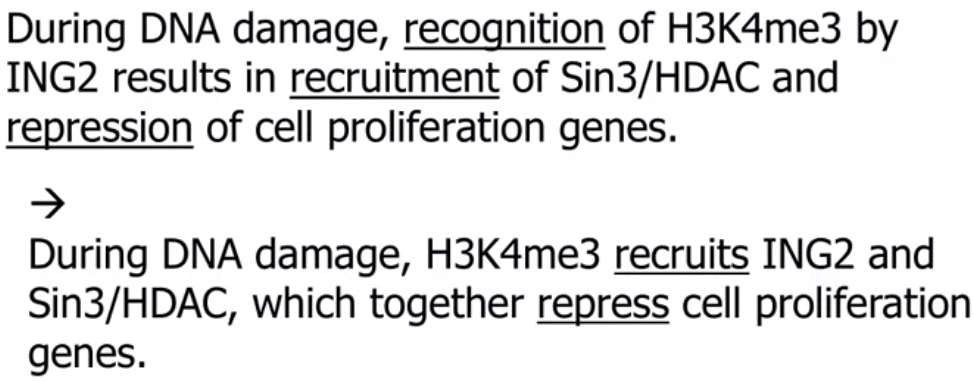

Use the active voice

Always prefer to active voice.

Format: subject + verb + object

Examples:

| Passive voice | Active voices |

|---|---|

| XXX could be observed | We could observe XXX |

| XXX were observed | We observed XXX |

| The activation of Ca++ channels is induced by the depletion of endoplasmic reticulum Ca++ stores. | Depleting Ca++ from the endoplasmic reticulum activates Ca++ channels. |

| Additionally, it was found that pre-treatment with antibiotics increased the number of super-shedders, while immunosuppression did not. | (Be direct) Pre-treating the mice with antibiotics increased the number of super-shedders while immunosuppression did not. |

Advantages of the active voice:

Emphasized author responsibility

- Passive: “No attempt was made to contact non-responders because they were deemed unimportant to the analysis.”

- Active: “We did not attempt to contact non-responders because we deemed them unimportant to the analysis.”

Improves readability:

- Passive: “A strong correlation was found between use of the passive voice and other sins of writing.”

- Active: “We found a strong correlation between use of the passive voice and other sins of writing. ”

- Active: “Use of the passive voice strongly correlated with other sins of writing.”

Reduces ambiguity

- Passive: “General dysfunction of the immune system at the leukocyte level is suggested by both animal and human studies.”

- Active: “Both human and animal studies suggest that diabetics have general immune dysfunction at the leukocyte level.”

Q: Is it ever OK to use the passive voice?

A: Yes! The passive voice exists in the English language for a reason. Just use it sparingly and purposefully. For example, passive voice may be appropriate in the methods section where what was done is more important than who did it.

Q: Since we are encouraged to use active voice, is it really OK to use "We" and "I"?

A: Yes, it is OK!

- The active voice is livelier and easier to read.

- Avoiding personal pronouns dose not make your sentence more objective.

- By agreeing to be an author on the paper, you are taking responsibility for its content. Thus, you should also claim responsibility for the assertions in the text by using “we” or “I”.

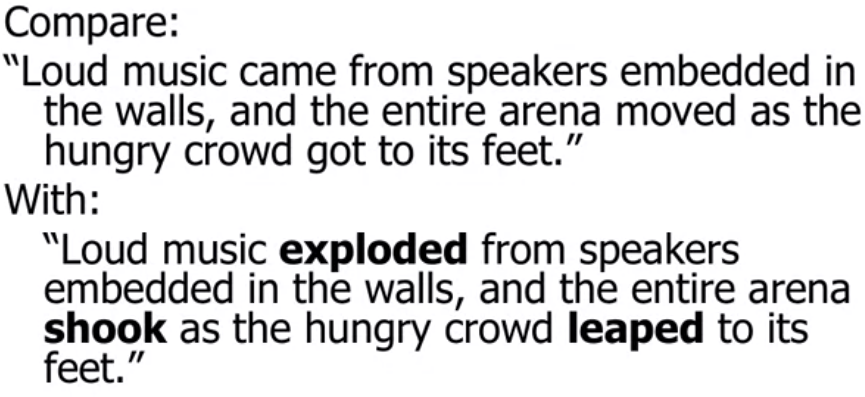

Write with Verbs

Use strong verbs:

- Verbs make sentences go!

- Pick the right verbs!

- Use “to be” verbs purposefully and sparingly.

- Don’t turn verbs into nouns: Don’t kill verbs by turning them into nouns.

- Don’t bury the mean verb: Keep the subject and main verb (predicate) close together at the start of the sentence.

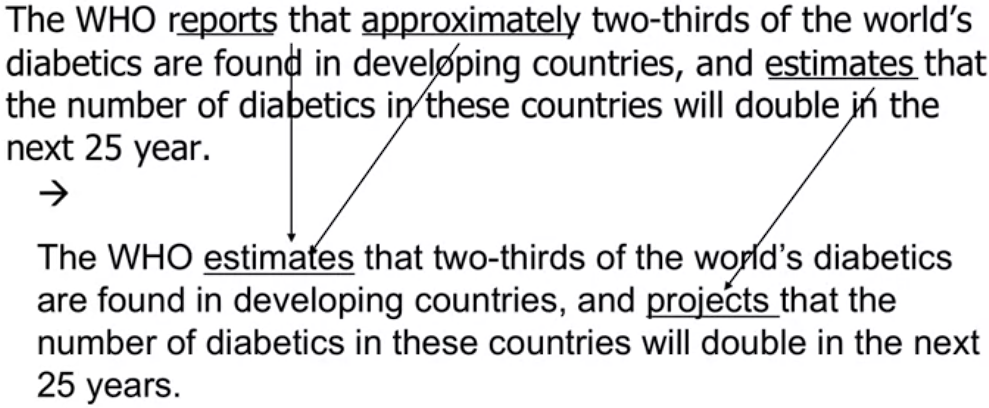

A Few Grammar Tips

- “data are” not “data is”: “data” is plural

- “affect” vs. “effect”: verb vs noun

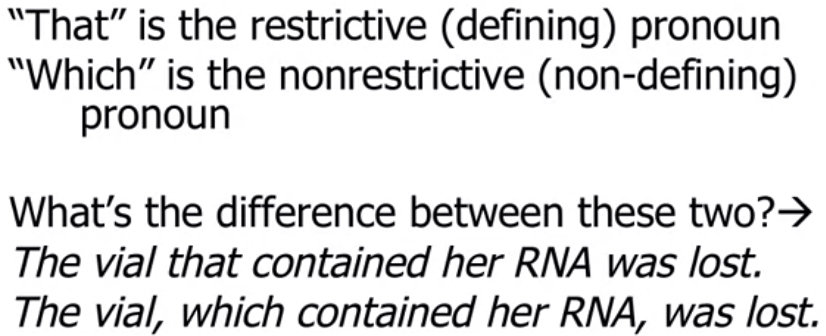

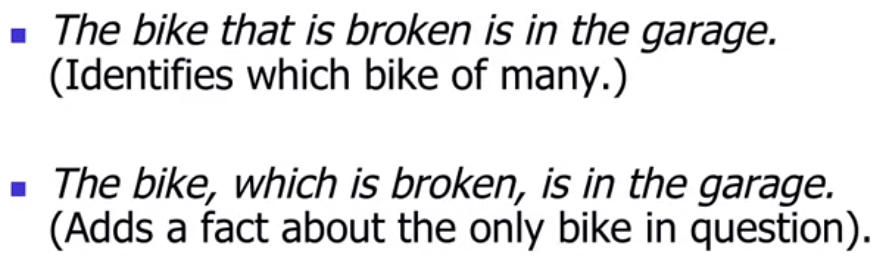

- “compared to” vs. “compared with”

- “that” vs. “which”

Section 3

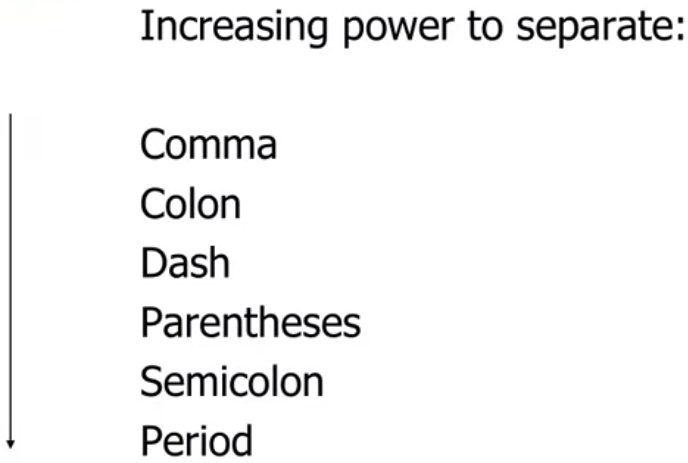

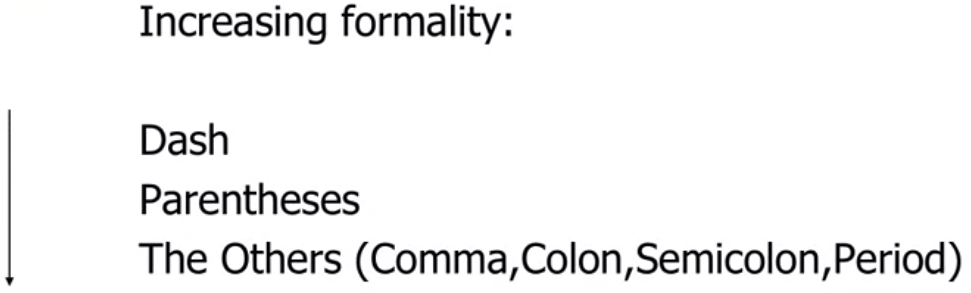

Semicolon ;

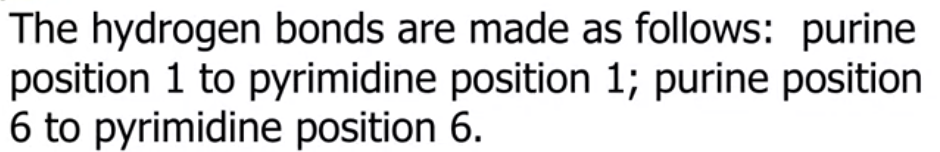

The semicolon connects two independent clauses.

Note: a clause always contains a subject and predicate; an independent clause can stand alone as a complete sentence.

Semicolons are also used to separate items in lists contain internal punctuation.

Parentheses ()

Parenthesis

Use parentheses to insert an afterthought or explanation (a word, phrase, or sentence) into a passage that is grammatically complete without it.

- If you remove the material within the parentheses, the main point of the sentence should not change.

- parentheses give the reader permission to skip over the material.

Examples:

- Example 1:

- Example 2:

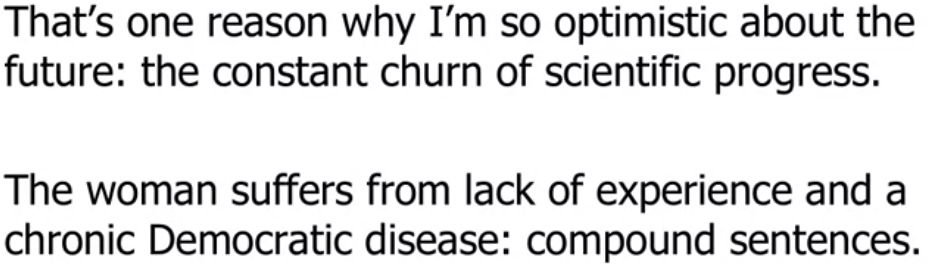

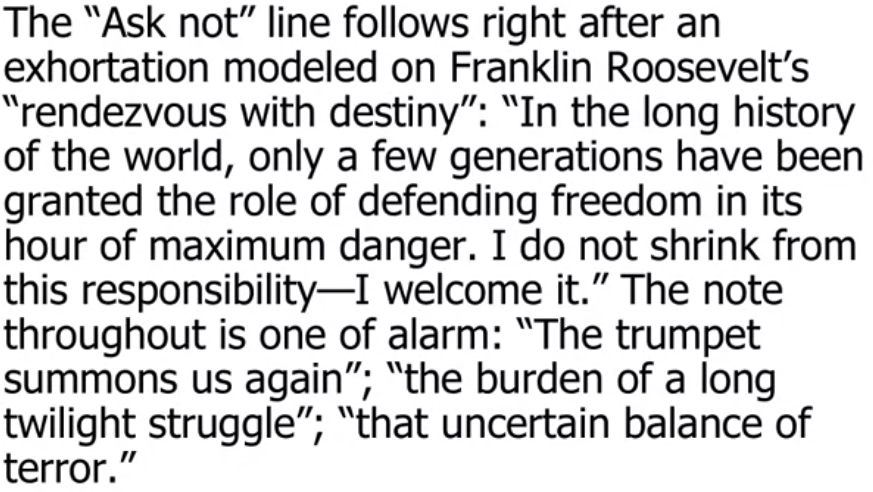

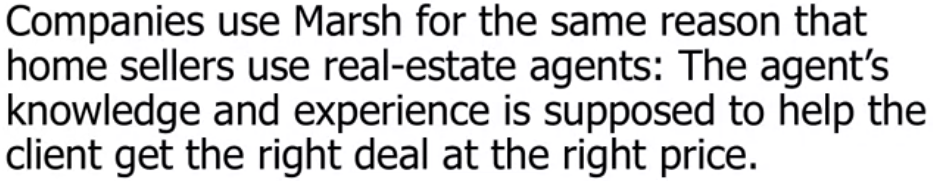

Colon :

Use a colon after an independent clause to introduce a list, quote, explanation, conclusion, or amplification

Examples:

- Example 1: list or explanation

- Example 2: explanation or amplification

- Example 3: quote, list of quotes

- Example 4: to amplify or extend. Use a colon to join two independent clauses if the second amplifies or extends the first

The rules of three’s (lists, examples): when list examples, three examples are best

Dash —

Use the dash to add emphasis or to insert an abrupt definition or description almost anywhere in the sentence. Just don’t overuse it, or it loses its impact.

Examples:

- Example 1: emphasis

- Example 2: emphasis and added information

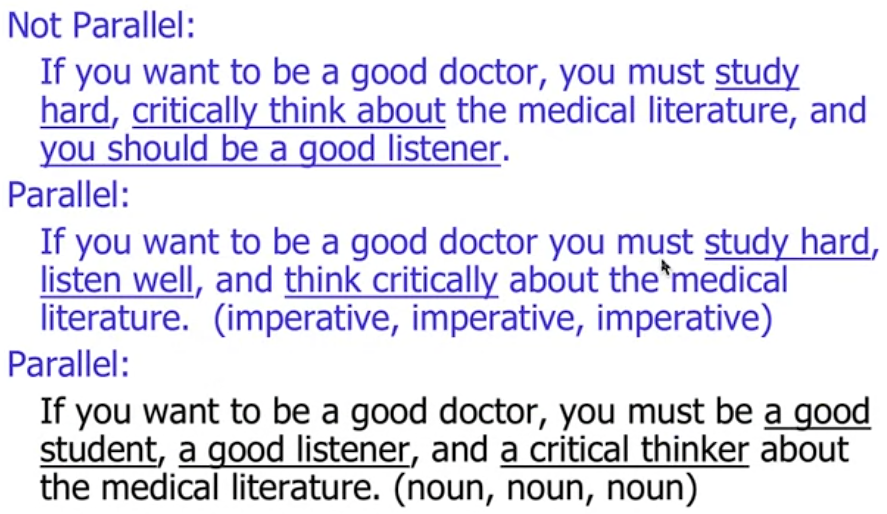

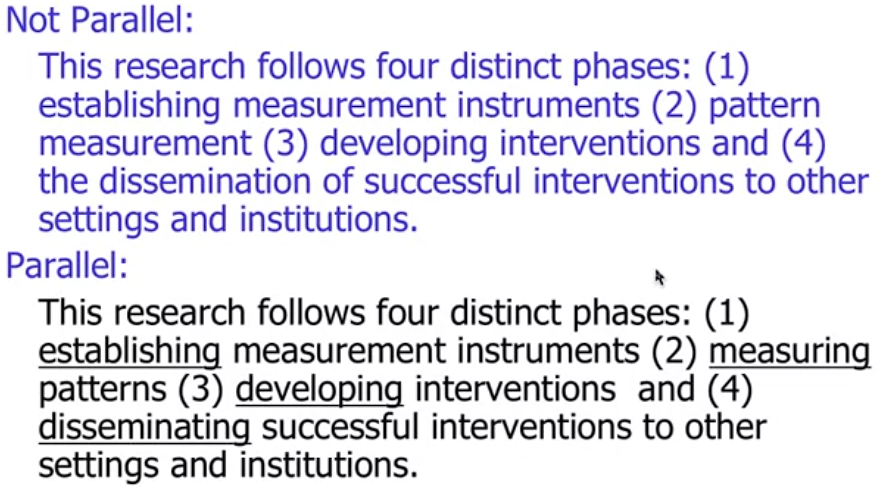

Parallelism

- Pairs of ideas joined by “and”, “or”, or “but” should be written in parallel form.

- Lists of ideas should be written in parallel form.

- You need to make a choice and stick to it! (choose a structure and follow it)

Examples:

- Example 1:

- Example 2:

Paragraphs

Paragraph-level tips:

1 paragraph = 1 idea

Give away punch line (conclusion) early.

Paragraph flow is helped by:

logic flow of ideas

- Sequential in time (avoid the Memento approach!)

- General

- Logical arguments (if a then b; a; therefore b)

parallel sentence structures

if necessary, transition words

Your reader remembers the first sentence and the last sentence best. Make the last sentence memorable. Emphasis at the end!

A Few More Tips

Repetition:

When you find yourself reaching for the thesaurus to avoid using a word twice within the same sentence or even paragraph, ask:

- Is the second instance of the word even necessary?

- If the word is needed, is a synonym really better than just repeating the word? (it is OK to repeat a word)

Acronyms/Initialisms:

- It’s OK to repeat words. Resist the temptation to abbreviate words simply because they recur frequently!

- Use only standard acronyms/initialisms (e.g., RNA). Don’t make them up!

- If you must use acronyms, define them separately in the abstract, each table/figure, and the text/ For long papers, redefine occasionally (as readers don’t typically read start to finish).

Section 4

Overview of the Writing Process

Pre-writing:

- Collect, synthesize, and organize information

- Brainstorm take-home messages

- Work out ideas away from the computer

- Develop a road map/outline

Writing the first draft:

- Putting your facts and ideas together in organized prose

Revision:

- Read your work out loud

- Get rid of clutter

- Do a verb check

- Get feedback from others

The Pre-writing Step

Get organized first!

- Don’t try to write and gather information simultaneously!

- Gather and oraganize information BEFORE writing the first draft.

Spend more time organizing and less time writing. It’s just plain less painful!

Develop a road-map:

- Arrange key facts and citations from literature into curde road map/outline BEFORE writing the first draft.

- Think in paragraphs and sections…

Brainstorm away from the computer:

Write on the go!

- While exercising

- While driving alone

- While waiting in line

- …

Work out take-home message

Organize you paper

Write memorable lines

Compositional organization:

Like ideas/paragraphs should be grouped

Don’t “Bait-and-Switch” you reader too many time: When dicussing a controversy, follow:

- arguments (all)

- counter-argumens (all)

- rebuttals (all)

The Writing Step

Tips for writing the first draft:

- Don’t be a perfectionist!

- The goal of the first draft is to get the ideas down in complete sentences in order.

- Focus on logical organization more than sentence-level details.

- Writing the first draft is the hardest step for most people. Minimize the pain by writing the first draft quickly and efficiently!

One more tip on making writing easier: Break your writing task into small and realistic goals

- My goal is to write 40 words today

- My goal is to write the first two paragraphs of the discussion section today

- …

Revision

Read your work out loud: The brain porcesses the spoken word differently than the written word!

Do a verb check: Underline the main verb in each sentence, watch for

- Lackluster verbs (e.g., There are many students who struggle with chemistry.)

- Passive verbs (e.g., The reaction was observed by her.)

- Buried verbs (e.g., A careful monitoring of achievement levels before and after the introduction of computers in the teaching of our course revealed no appreciable change in students' performances.)

Don’t be afraid to cut! Watch for:

- Dead weight words and phrases (it should be emphasized that)

- Empty words and phrases (basice tenet of, importan)

- Long words or phrase that could be short (muscular and cardiorespiratory performance)

- Unnecessary jargon and acronyms

- Repetitive words or phrase (teaches clinicians/guides clinicians)

- Adverbs (very,really, quite, basically)

Do a organizational review

In the margins of your paper, tag eachparagraph with a phrase or sentence thatsums up the main point. Then move paragraphs around to improve logical flow and bring similarideas together.

Get outside feedback

Ask someone outside your department to read your manuscript.

Without any technical backgroud, they should easily grasp:

- the main findings

- take-home messages

- significance of your work

Ask them to point out particularly hard-to-read sentences and paragraphs!

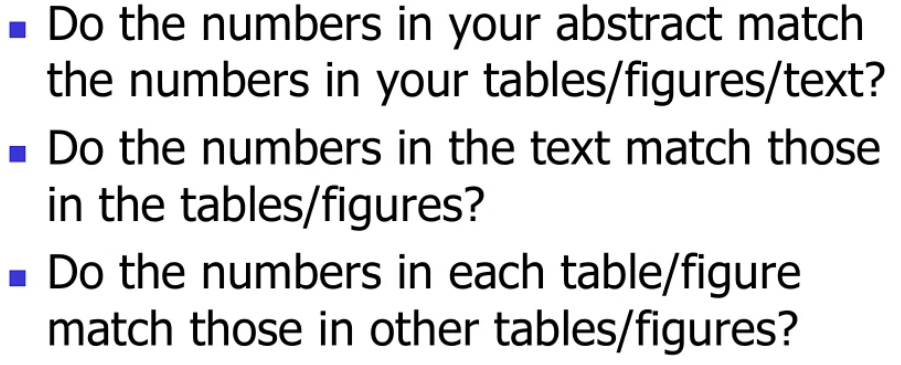

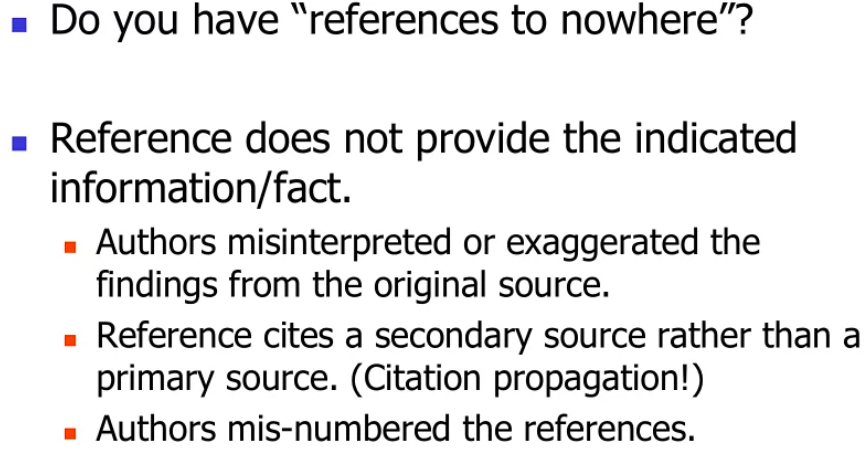

Checklist for the Final Draft

- Check for consistency

- Check for numerical consistency

- Check your references

Section 5

Recommended order for writing an original manuscript

- Tables and Figures

- Results

- Methods

- Introduction

- Discussion

- Abstract

Tables and Figures

Tables and figures are the foundation of your story! Editors, reviewers, and readers may look first (and maybe only) at titles, abstracts, and tables and figures! Figures and tables should stand alone and tell a complete story. The readers should not need to refer back to the main text.

Tips on Tables and Figures:

- Use the fewest figures and tables needed to tell the story.

- Do not present the same data in both a figure and a table.

Table Title:

- Identify the specific topic or point of the table.

- Use the same key terms in the table title, the column headings, and the text of the paper.

- Keep it brief!

Results

The results section should:

Summarize what the data show

- Point out simple relationships

- Describe big-picture trends

- Cite figures or tables that present supporting data

Avoid simple repeating the numbers that are already available in tables and figures

Tips for writing Results:

Break into subsections, with headings (if needed)

Complement the information that is already tables and figures

- Give precise values that are not available in the figure

- Report the percent change or percent difference if absolute values are given in the table

Repeat/highlight only the most import numbers

Don’t forget to talk about negative and control results

Reserve the term “significant” for statistically significant

Reserve information about what you did for the methods section

- In particular, do not discuss the rationale for statistical analyses within the Results section

Reserve comments on the meaning of your results for the discussion section

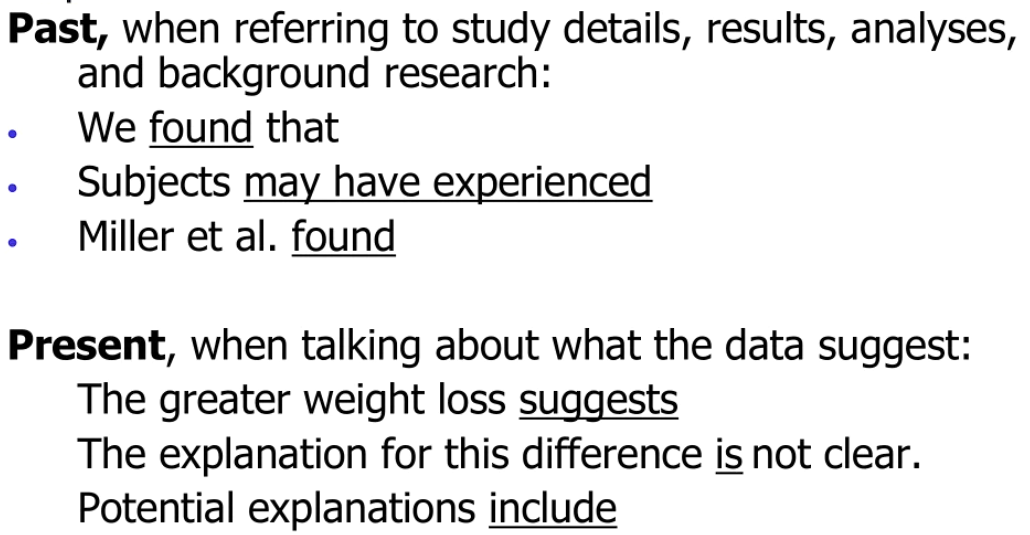

Q: What verb tense do I use?

A: Use past tense for completed actions. Use present tense for the assertions that continue to be true, such as what the table show, what you believe, and what data suggest.

Use the active voice: More lively! (use “we”)

Methods

Give a clear overview of what was done

Give enough information to replicate the study (like a recipe!)

Be complete, but make life easy for your reader!

- Break into smaller sections with subheadings

- Cite a reference for commonly used methods, instead of introduce them detailly

- Display in a flow diagram or table where possible

You may use jargon and the passive voice liberally in the methods section

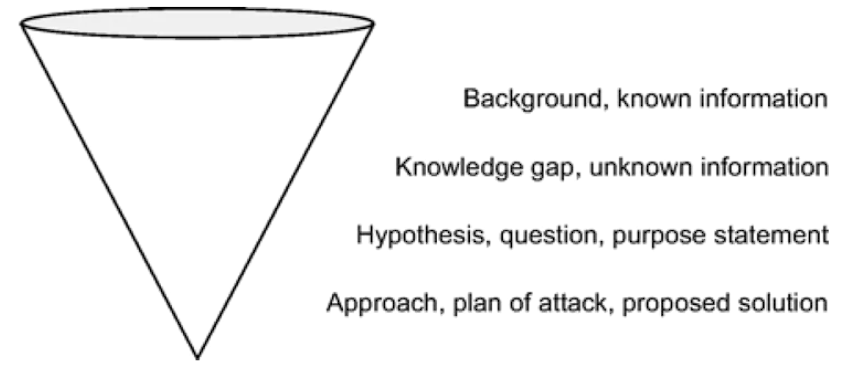

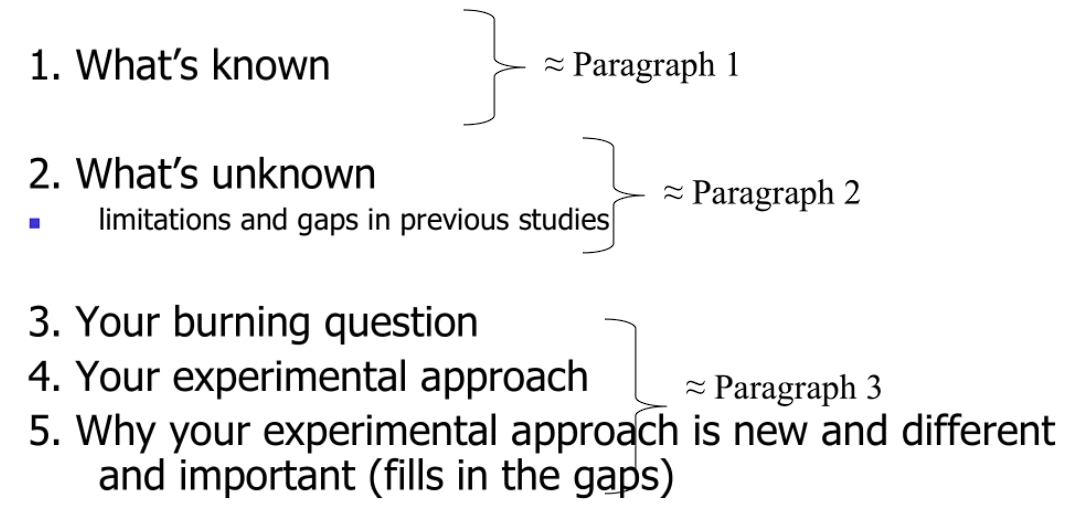

Introduction

- Good News: The introduction is easier to write than you may realize!

- Follows a fairly standard format

- Typically 3 paragraphs long: Recommended range: 2-5

- It is not an exhaustive review of you general topic: should focus on the specific hypothesis/aim of your study

Tips for writing an Introduction:

Keep paragraph short

Write for a general audience

- clear, concise, non-technical

Take the reader step by step from what is known to what is unknown. End with your specific question

Emphasize how your study fills the gaps

Explicitly state your research question/aim/hypothesis

Do not answer the research question

Summarize at a high level! Leave detailed descriptions, speculations, and criticisms of particular studies for the disscussion.

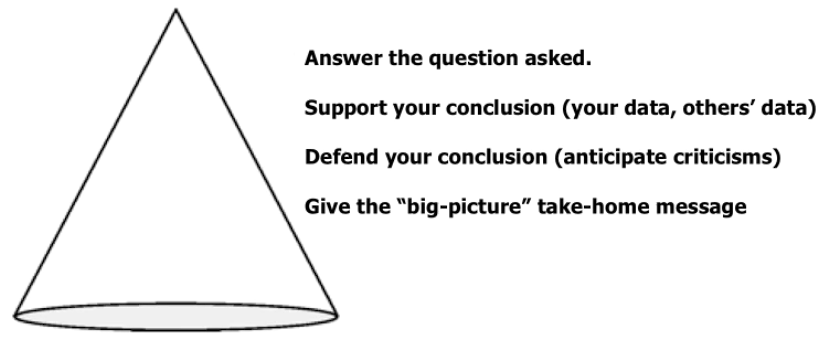

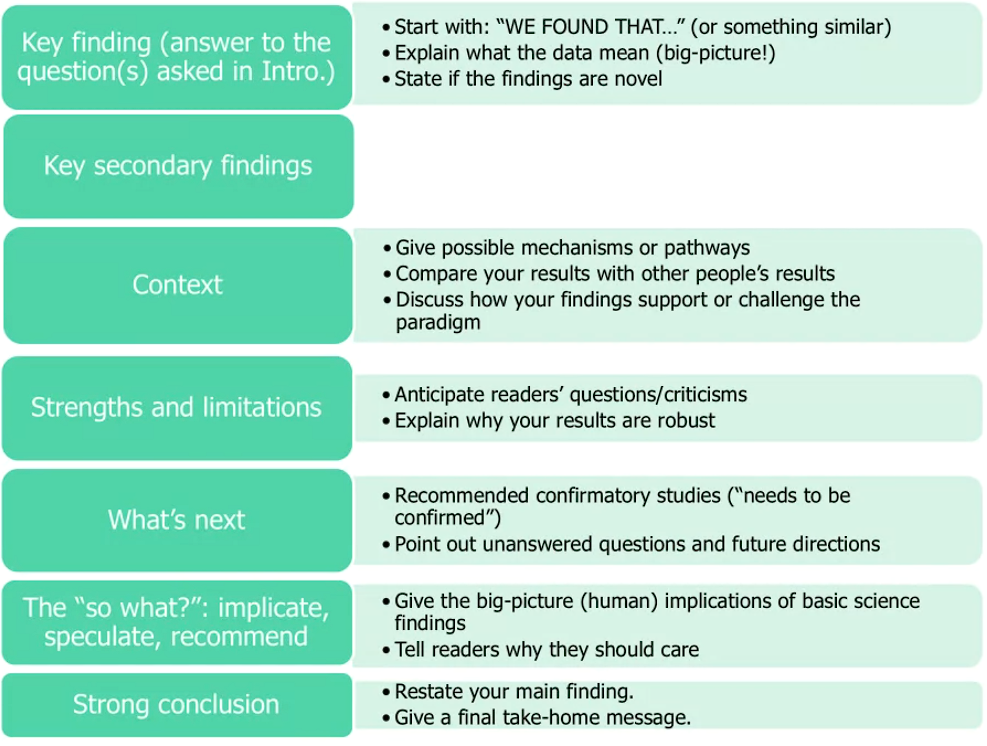

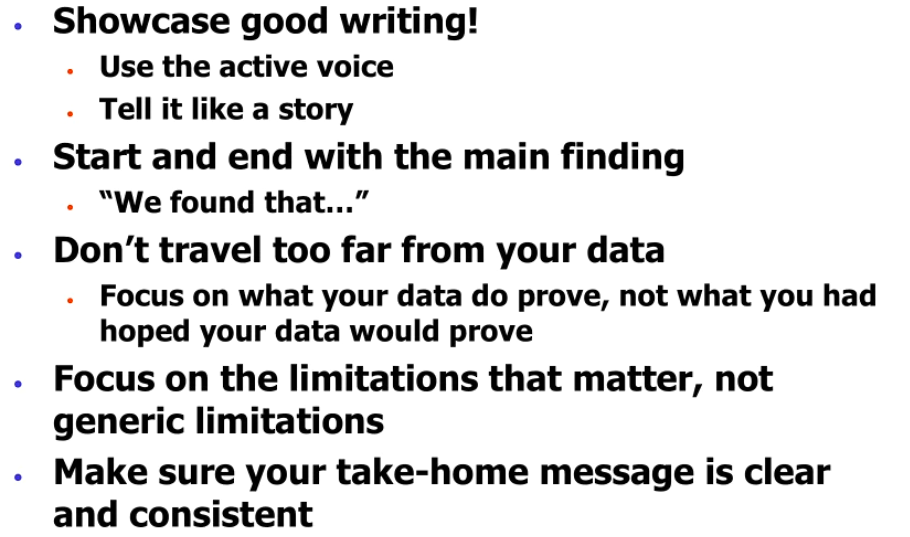

Discussion

Invert the cone!

Tips:

Verb tense:

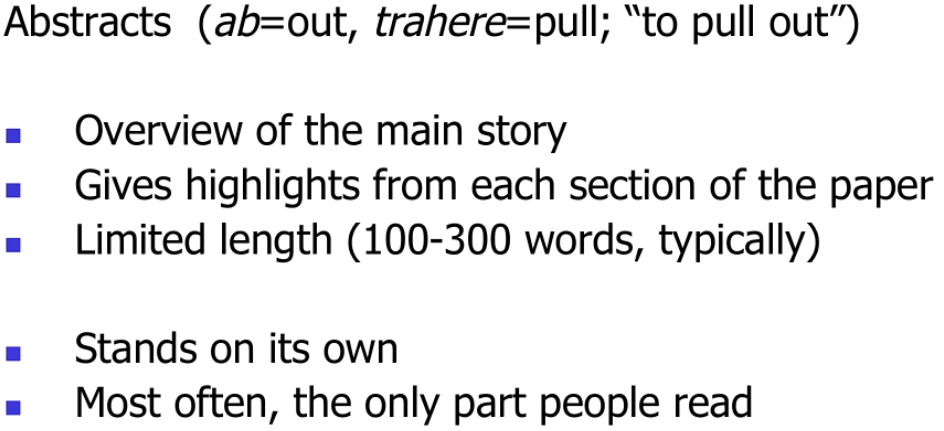

Abstract

General structure:

- Background

- Question/aim/hypothesis: “We asked whether,” “We hypothesized that,” ..etc

- Experiments: Quick summary of key materials and methods

- Results: key results found, minimal raw data

- Conclusion: The answer to the question asked/take-home message

- Implication, speculation, or recommendation

Section 6

Plagiarism

Passing off other people’s writing (or tables and figures) as your own, including:

- Cutting and pasting sentences or even phrases from another source

- Slightly rewriting or re-arranging others’ words

- “borrowing” material from sites like Wikipedia

When writing about others’ ideas/work:

- You must understand the material well enough to put it in your own words!

- Work from memory

- Draw your own conclusions

- Do not mimic the original author’s sentence structure or just re-arrange the original author’s words

Self-plagiarism and duplication: Recycling your own writing or data, including:

- Copying or only slightly rewriting text from your own previously published papers.

- Adding new data to already published data and presenting it as new results.

- Submitting identical or overlapping data to multiple journals.

Authorship

Who gets authorship?

- Any authors listed on the paper’s title page should take public responsibility for its content.

In what order?

- Order implies authors’ relative contributions (with exception of the senior author position)

- The senior author (head of the lab or research team) often appears as the last-listed author

- Papers may have dual first authors

- For fairness, alphabetical or reverse alphabetical order may be used if researchers have contributed equally

- Large working group may be cited as a group

Acknowledgements

- Funding sources

- Contributors who did not get authorship (e.g. offered help)

Submission process

Identify a journal/conference for submission (ideally before writing!)

Follow the online “instructions for authors” for writing and formatting the manuscript

Submit your manuscript online (corresponding author)

- All authors must fill out and sign copyright transfer and conflict of interest forms (often done offline)

Possible outcomes: accepted; accepted pending minor revisions; rejected but re-submission possible; no resubmission possible…

Revision and resubmission: re-submit with cover letter that addresses reviewers critiques point by point

Doing a peer review

- Assume there is some poor graduate student on the other end who did all the work, and whose confidence and career depend on your critique

- Tone matters!

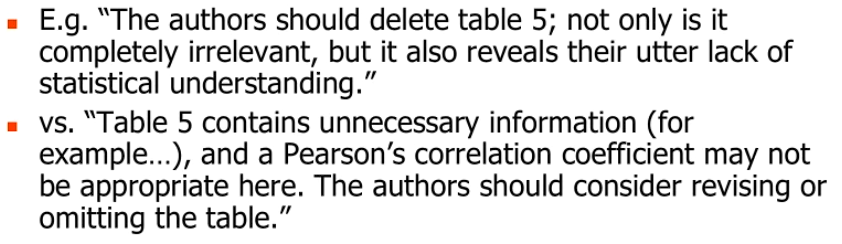

- Avoid criticizing the authors! Criticize the work

- Avoid generalization; point out specific errors

- Use positive instead of negative language where possible: “The paper is poorly written.” vs. “The writing and presentation could be improved. For example…”

- Avoid ”lecturing” to the authors

Types of peer review:

- Single-blind

- Double-blind

- Post-publication peer review: blogs, online comments, etc.

Predatory Journal

Just do not submit your paper to predatory journal, unless you mean to do that.

Section 7

Main idea for section 7 and later section 8: show, don’t tell

Writing Review Articles

Goals:

- Synthesize and evaluate the recent primary literature on topic.

- Summarize the current state of knowledge on a topic.

- Address controversies.

- Provide a comprehensive list of citations.

Tips for review articles:

- Start with a more broad search, and then narrow it.

- Clearly define your thesis or theme.

- Invest time getting organized!

- Divide the review into sections with separate headings.

- Consider putting information in tables, figures, and/or sidebars.

- Write for a broad audience.

Structure of a review article:

Abstract

Introduction: Clearly state the aim of the review.

The body of the paper

- Divide into sections.

- Summarize the literature, organized based on methodology or theme.

- Analyze, interpret, critique, and synthesize studies.

Conclusion and future directions

- What recommendations can you make?

- What gaps remain in the literature? What future studies would help fill in these gaps?

Literature cited

Writing letters of recommendation

Things to consider:

- It’s OK to decline if you cannot write a strong letter.

- Take into account the competitiveness of position or award.

- Never ask students to draft their own letters.

The candidate should provide:

- CV or resume

- Information about the position or award

- The deadline

- Specific information about

Formatting:

- Format it like an old-fashioned letter (date, address of the committee, etc.)

- Use letterhead (or the electronic version of that)

- Avoid generic greeting such as “to whom it may concern.” Rather, address it to a person (if known) or “XX admission committee” or “XX scholarship committee”

Content:

Introduction:

“I am pleased/delighted/thrilled to recommend XX for YY.” “It’s pleasure to recommend XX for YY.”

How do you know the candidate? How long have you known the candidate?

1-2 sentences overview

- Highest praise: “She is one of the most brilliant and accomplished students that I have taught to date.”

- Typical praise: “I’ve found her to be a diligent student and researcher. I’m confident that she would be an asset to your research team.”

Body:

Use clear, concise, engaging language!

The length of letter matters!

Address qualities relevant to the position/award, such as:

- Quantitative skills

- Communication skills

- Ability to work with others

- Initiative

- Ability to prioritize tasks

- Creativity

- Attributes of a “good citizen”

Give specific examples and stories. “Show, don’t tell.”

Quantify and compare

Point out extenuating circumstances (if applicable)

Bold/underline to add emphasis

If possible, quote other may helpful materials

Conclusion:

- Highest praise: “In summary, XX is a star in all aspects. If there;s anything else I can do to support her application, please don’t hesitate to contact me.”

- Typical praise: “I highly recommend XX for this position. If you have any further questions, I would be happy to expand further on my comments.”

Be cautious:

- When a letter focuses more on the recommender, class, or project than on the candidate, this is a red flag.

- It’s OK to highlight strengths from the student’s CV, but don’t simple repeat what’s on the CV.

Tips for recommendees:

Approach potential letter writers at least several weeks in advance of the deadline.

Choose your recommenders carefully.

Take “no” for an answer.

Avoid recommenders who ask you to draft your own letter.

Make life easy for your letter writer

- Provide them with your CV; offer to meet with them; give them clear and easy instructions on how to submit the letter; provide a link to information about the position or award

Personal statement

Tips for personal statement:

Make it personal

- Speak from the heart

- Reveal who you are

- Strive for flair, not ‘blah’

Give specific examples and stories: Show, don’t tell.

Don’t read your CV line by line: highlight relevant experiences

Avoid big words you don’t understand and avoid cliches

Show interest in/flatter your readers

Explain gaps and failures: Don’t ignore these in hopes that reviewers won’t notice the issue!

Elements:

Opening/Lead

- Start strong!

- Be creative

- Be descriptive or tell a story

- Impart who you are and what matters to you

- Don’t be boring

- It’s OK if it’s a little long if it’s compelling

Body of the Essay

Where do you want to go?

What experience have led you to this point?

What makes you a strong candidate?

- address weakness, and turn them into strengths.

Why this specific program/institution/fellowship?

Conclusion

- End strong!

- Consider circling back to your opening story or description

Section 8

Talking with the media

Being interviewed by a Journalist:

Q: What the journalist is waiting to hear, and will use in his/her article:

A:

- take-home message

- how your research affects people (i.e., their readers)

- what’s different or new about your results (the “news hook”)

- colorful prose

- interesting stories (anecdotes)

- paradox/irony/surprise

- people-focused stories

- historical facts/the development of the idea

- sweeping comments about the significance of the work (makes a good first quote)

- controversy/criticism or laudatory praise, if you are being asked to comment on a peer’s research

Q: What is the job as the interviewee?

A:

Be prepared.

Avoid jargon. Pretend that you are talking to your aunt/uncle/grandmother/grandfather.

Give the journalist clear take-home mesages.

Anticipate confusions/misinterpretations; and explain them away.

Give a clear statement of the key limitations of the work.

Think carefully about how to present data/numbers in a way that is understandable to a general audience

Make unites understandable

Present risks in an essay-to-understand, transparent way.

- Whole numbers are easier to understand than fractions and percents.

- Relative risk can be high even if absolute risk is low.

Writing for general audiences

Whether writing for a general audience or other scientists, you should:

- Be concise.

- Be clear.

- Be engaging.

When writing for a general audience, you must additionally:

- Start with the take-home message.

- Recognize and avoid jargon: this includes not just technical terms, but also “scientist-speak.”

- Unpack the science: Your audience may be unfamiliar with basic scientific concepts that you take for granted. You need to explain the science—without handwaving!

- Filter out unnecessary details: Lay audiences don’t need to know all the nitty-gritty scientific details.

- Get there faster

- Tell a story: Use story-telling techniques to set a scene, (appeal to the 5 senses), focus on characters (human beings!), follow a plot (drama and suspense).

Writing a science news story

- Who? What? Where? When? Why? How?

Any good news story provides answers to each of these questions.

News stories follows a basic formula (just as scientific journal articles do)…

Lead (also spelled “lede”)

- The first paragraph

- Grabs the reader’s attention

- Imparts the heart of the matter (simple and focused)

Guidelines for lead:

- 1-2 sentences

- Aim for <35 words

- Use the main verb to carry the main news, and use action verbs

- Give complementary, but different information than the headline

- Provide some, but not necessarily all, of the 5 W’s and 1 H

Nut Graf

Shortly after the lead paragraph, the so-called ‘nut graf’ flushes out the story: the 5W’s and the H. Occasionally, the nut graf is hidden-contained within the lead or strewn throughout several paragraphs. But usually, it’s identifiable.

First quote (3-6 paragraphs down)—brings in the human element

The fun part of news writing! The interview doesn’t involve any ‘writing’ on your part—just eliciting good quotes and strategic placement.

- Give a human dimension to the story

- Provide evidence

- Provide opinion

- Provide color and flavor

- Flush out the main idea

- Move the story along

Body of the story

- What was done before

- What was done in the study—key experiments/key findings

- Implications/caveats

Filter out less important details! Use quotes to add flavor and break up the story!

Kicker

- The ending.

- Leaves the reader felling satistied.

- Often circles back to the lead.

- A quote can be effective.

Prefer “said” (or “says”) to most other possibilities, such as “noted” and “remarked,” which have particular connotations

e.g., Noted implies that whatever the person’s statement was fact.